In 1713, Nova Scotia was ceded to the British Crown. In 1721, "a General Court or Court of Judicature" was established at Annapolis Royal, consisting of the Governor and his Council. This court continued to exercise civil and criminal jurisdiction until the establishment of a regular court in 1749, after the founding of Halifax. A committee of the Council in 1749 reported that the judicial system of Virginia was the "most proper to be observed in the Province." As such, two courts were established:

The General Court, composed of the Governor and Council, had civil, criminal and exchequer jurisdiction, as well as the authority to hear appeals from the County Court. A County Court, composed of five Justices of the Peace (sitting monthly), had jurisdiction over common law matters across the whole province, except for those punishable by death or outlawry. The name of this court was changed in 1752 to the "Inferior Court of Common Pleas".

Three of Canada's key principles of democracy were first established here in Nova Scotia: a truly independent court, an elected government and freedom of the press. The country's first independent court was established in Nova Scotia in 1754 under The Hon. Jonathan Belcher, the Chief Justice and only judge at the time. Four years later, in 1758, Canada's first elected assembly of representatives of the people was established. In 1835, freedom of the press was first legally recognized by a Canadian Court — the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia — in the famous Joseph Howe trial.

Click on the headings below for more detailed information on the Courts' history.

Main navigation: show child menu items

The Nova Scotia Supreme Court is the first superior court to apply the common law within the boundaries of what is now Canada. The common law of Britain came to the province after the French ceded mainland Nova Scotia to the British in 1713, under the Treaty of Utrecht. In 1721, in response to “the dayly cry ... for Justice” from the inhabitants, the British established a General Court at the capital, Annapolis Royal. Based on a model used in Virginia, the court consisted of the governor and members of his council. This court continued to hear all civil and criminal cases until the founding of Halifax in 1749.

Colonel Edward Cornwallis who became governor when Halifax was established, was authorized to create laws “as near as may be agreeable” to those of Britain. A two-tier court system was put in place, with the General Court retained to hear all criminal cases. It also heard appeals of the decisions of the lower court in civil disputes involving more than £300. Concerns about the legitimacy of legal decisions made by laymen, coupled with complaints that judges of the lower court were applying New England law, prompted the British authorities to appoint a lawyer to serve as chief justice. Jonathan Belcher, a New Englander who had practiced law in England and Ireland, was sworn in as chief justice of the newly established Supreme Court on October 21, 1754.

When Nova Scotia was granted an elected assembly in 1758, one of the first acts passed confirmed all “sentences, verdicts and judgments” of the Supreme Court. A growing caseload prompted the appointment of two laymen, Charles Morris and John Collier, as assistant judges in 1764, but until 1773 they could only hear cases in tandem with the chief justice. The court began sitting once or twice a year in communities outside Halifax in 1774, and this circuit system was extended to the entire province by 1851.

In the late 1780s, a controversy dubbed “The Judges’ Affair” rocked the court. British officials had difficulty finding a permanent replacement for Belcher, who died in 1776. The senior assistant judge, Isaac Deschamps, was in charge for several years despite his lack of formal legal training. Lawyers among the Loyalist refugees newly arrived from the American colonies launched a campaign to impeach Deschamps and the other assistant judge, James Brenton, accusing them of incompetence and bias. The Assembly investigated but Lieutenant-Governor John Parr and his council cleared both judges and dismissed the allegations as “groundless and scandalous.” The complaints resurfaced in 1790 and the Assembly voted to impeach Deschamps and Brenton for “high crimes and misdemeanours.” The Privy Council of the British government reviewed the allegations and, in a 1792 report, exonerated both judges and condemned their detractors. Since 1809, however, all judges of the Supreme Court have been required to have practiced law for at least ten years.

The court grew as the province’s population increased. A fourth judge was added in 1810 and six years later an associate judge was appointed to preside over cases outside Halifax. In 1841 the province’s lower court, the Inferior Court of Common Pleas, was abolished and the Supreme Court assumed jurisdiction over most criminal and civil cases, leaving minor offences and civil disputes in the hands of local justices of the peace.

In 1848, Nova Scotia became the first province granted responsible government – a form of parliamentary government requiring the party in power to have the confidence of a majority of the elected members of the Assembly. Judicial reforms including granting independence to judges of the Supreme Court, who could only be removed from office through a vote of both the Assembly and the Legislative Council.

Upon Confederation in 1867, the federal government assumed the power to appoint Supreme Court judges. Two judges were added to the court in 1870, bringing the total to seven. A County Court was established in 1874 to ease the caseload of the Supreme Court – County Court judges in seven districts heard cases without juries, improving access to justice and allowing for speedier trials. In 1875, the Supreme Court of Canada was created to hear appeals of rulings of superior courts in Nova Scotia and other provinces.

Proposals for court reform surfaced in the 1920s, when Attorney General Walter J. O’Hearn put forward legislation to abolish grand juries and create a separate court of appeal. No action was taken, however, and the grand jury – a group of citizens empaneled to review allegations in criminal cases – persisted in Nova Scotia until 1984, long after it had been abolished in the rest of Canada. The Supreme Court continued to sit as a group to consider appeals until the creation of distinct Trial and Appeal divisions in 1966.

The court recorded a series of firsts beginning in the mid-1960s. Vincent Pottier became the first Acadian named to Supreme Court in 1965; J. Louis Dubinsky, the first member of the Jewish community to serve on the court, was appointed two years later; and Justice Constance Glube – the first woman appointed to the court, in 1977 – was promoted to chief justice of the Trial Division in 1982, becoming the first woman to serve as chief of a Canadian superior court.

During the 1980s, however, the Supreme Court itself was put on trial. Federal Justice Minister Jean Chretien referred the case of Mi’kmaq teenager Donald Marshall, Jr., who served 11 years in prison for a 1971 murder in Sydney, to the Appeal Division for review. The court acquitted Marshall but insisted any miscarriage of justice was “more apparent than real” despite growing evidence of misconduct by police and prosecutors. The Nova Scotia government established a royal commission, headed by three out-of-province judges, to investigate the case and the province’s justice system. The commission’s 1990 report condemned systemic racism and political influence in the province’s justice system. Reforms have included giving police the power to decide whether to file criminal charges and the creation of the only Canadian prosecution agency that operates independently of government. The Canadian Judicial Council investigated the five Appeal Division judges who said Marshall was to blame for his wrongful conviction and, while critical of their conduct, the council found no grounds to justify their removal.

More court reforms were undertaken in the 1990s. On the recommendation of the Nova Scotia Court Structure Task Force, the County and Supreme courts were merged to create a bench of 25 judges at the trial level. The Appeal Division was reconstituted as the Court of Appeal, with eight judges. In 1999 a Family Division of the court, with eight judges, was established to deal with divorces and other family law cases in the Halifax and Sydney areas. There are plans to extend its jurisdiction to all parts of the province, replacing the Family Court that still sits in other centres.

The Supreme Court has emerged as a leader in Canada in judicial education and accountability to the public. It spearheaded a program that enables lawyers to provide confidential assessments of the performance of its judges, and created a central administrative office that serves all courts in the province – the first of its kind in Canada. It was one of the first courts to establish a media liaison committee, giving judges and journalists a forum to resolve disputes over court access and problems arising from media coverage. The province’s guidelines for media access and an Internet-based system for notifying the media of applications for publication bans have become models for other provinces. Nova Scotia is also a leader in the creation of restorative justice programs that impose alternative forms of punishment and seek to reconcile offenders and their victims.

As of 2004 the Court of Appeal consisted of the Chief Justice of Nova Scotia (who is also the Chief Justice of the Court of Appeal) and seven other judges. Semi-retired (supernumerary) judges may also form part of the court at any given time. The Supreme Court comprised a chief justice, an associate chief justice and twenty-one judges. There were also six supernumerary or semi-retired judges.

-------

Sources: Barry Cahill and Jim Phillips, “The Supreme Court of Nova Scotia: Origins to Confederation,” and Philip Girard, “The Nova Scotia Supreme Court: Confederation to the 21 st Century,” in Girard, Phillips and Cahill, eds., The Supreme Court of Nova Scotia 1754-2004: From Imperial Bastion to Provincial Oracle (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004); The Supreme Court of Nova Scotia and Its Judges: 1754-1978 (Halifax: Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society, 1978).

1721 – In response to “the dayly cry ... for Justice” from the inhabitants of Annapolis Royal, the British established a court based on a model used in Virginia. The governor and his Council presided over criminal cases and civil disputes.

1749 – Halifax founded as the new Nova Scotia capital. Colonial administrators authorized the governor, Col. Edward Cornwallis, to create laws “as near as may be agreeable” to those of Britain. A two-tier court system was put in place, with the General Court, made up of the governor and the Council, as the highest court in the colony. The General Court had the power to hear all criminal cases but none of its members had legal training. It also heard appeals of the decisions of the lower court, the Inferior Court of Common Pleas, in disputes involving more than £ 300.

1754 – Concerns about the legitimacy of legal decisions made by laymen, coupled with complaints that justices of the lower court were applying New England law, led to demands for the appointment of a trained lawyer to serve as chief justice. Jonathan Belcher was sworn in as chief justice of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court on Oct. 21. The court’s jurisdiction spanned the entire colony, which grew to include Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick after the Treaty of Paris ended the war with France in 1763.

1758 – Nova Scotia was granted an elected assembly. One of the first laws passed confirmed all “sentences, verdicts and judgments” of the Supreme Court.

1764 – Two laymen, Charles Morris and John Collier, appointed as assistant judges, but they were restricted to hearing cases only with the assistance of the chief justice.

1769 – Prince Edward Island made a separate colony.

1773 – Assistant judges were authorized to hear cases without the chief justice.

1774 – An influx of settlers after 1759 brought demands for the Supreme Court to hear cases Supreme Court Circuit was created with the Supreme Court Circuit Act of 1774outside Halifax. The Supreme Court Circuit Act of 1774 provided that a judge would travel twice a year to Annapolis, Kings and Cumberland counties to hold court. The circuit system was extended as the colony grew, with sittings once or twice a year in all counties by 1851.

1784 – New Brunswick and Cape Breton established as separate colonies, each with its own supreme court.

1787 – Lawyers among the Loyalist refugees from the American colonies led a campaign to impeach assistant judges Isaac Deschamps and James Brenton, accusing them of incompetence and bias. The Assembly conducted and investigation but the Council cleared both judges and dismissed the allegations as “groundless and scandalous.”

1790 – The so-called “Judges Affair” was revived. The Assembly passed seven articles of impeachment accusing Deschamps and Brenton of “high crimes and misdemeanours” and demanded their dismissal. The Privy Council of the British government reviewed the allegations and, in a 1792 report, cleared both judges and condemned the actions of their detractors.

1809 – The Supreme Court Act stipulated that judges must have legal training. Candidates were required to have been lawyers for at least ten years and to have practiced law for at least five years immediately before their appointment.

1810 – A fourth judge added to the Supreme Court.

1816 – The post of associate circuit judge was created to deal with the expanded circuits and the growing number of cases outside Halifax, bringing the court to five judges.

1820 – Cape Breton annexed to Nova Scotia and becomes part of the Supreme Court circuit.

1825 – Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society founded, only the second professional organization for lawyers in British North America.

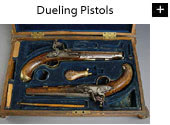

1830 – Richard John Uniacke Jr., acquitted of murder in 1819 after killing an opponent in a duel, became the first Nova Scotia-born judge of the Supreme Court.

1841 – Abolition of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas left the Supreme Court with jurisdiction to hear most criminal and civil cases, other than minor offences and disputes dealt with by local justices of the peace.

1848 – The granting of responsible government (a system requiring cabinet ministers to have the confidence of a majority of the assembly) also brought reform of the judiciary. The Nova Scotia government was given the power to appoint the chief justice and all future Supreme Court judges were granted independence. Judges served “during good behavior” and could only be removed from office through a vote of both houses of the legislature, the Assembly and the Legislative Council.

1855 – Court of Chancery, which specialized in foreclosures and applied legal concepts known as equitable principles, was abolished. The Supreme Court assumed jurisdiction over legal actions based on equity as well as the common law.

1855 – Volume One of the Nova Scotia Reports published, making the Court’s precedents widely available to lawyers. The initial volume was a collection of judgments handed down from 1834 to 1851.

1860 – The Supreme Court sat for the first time in the newly built Halifax County courthouse on Spring Garden Road.

1863 – The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain became the final court of appeal for Nova Scotia civil cases. The highest appeal court within Nova Scotia continued to be the Supreme Court sitting in banco – panels of judges reviewing decisions made by their colleagues at the trial stage.

1867 – Nova Scotia one of four colonies to merge at Confederation.

1870 – Two judges added to the court, bringing the total to seven.

1875 – The Supreme Court of Canada created to hear appeals of rulings of Nova Scotia Supreme Old Supreme Court of Canada - 1876, courtesy of the Supreme Court of Canada)Court and other provincial superior courts, with a final appeal still possible to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Exchequer Court of Canada (now the Federal Court) also established.

1877 – The County Court, established in 1874 to ease the caseload of the Supreme Court, begins hearing cases, The province is divided into seven districts, each with a County Court judge to hear cases without juries, improving access to justice and providing speedier trials.

1883 – Dalhousie Law School founded in Halifax, the oldest university-affiliated law school in the Commonwealth.

1889 – Federal Speedy Trials Act allows most offences – except the most serious, such as murder – to be heard without a jury in County Court, diverting more criminal cases from the Supreme Court.

1890 – The court established a rule that the judge who presided at trial could not take part in the appeal without the agreement of a majority of the other judges.

1916 – Joseph Chisholm became the first graduate of Dalhousie Law School to be appointed to the court. He was appointed chief justice in 1931.

1918 – Frances Fish admitted to the Nova Scotia bar, becoming the first woman entitled to practice law in the province.

1923 – Attorney General W.J. O’Hearn put forward legislation to overhaul the court system, abolish grand juries and create a separate court of appeal, but none of the initiatives were implemented.

1929 – With economic conditions worsening on the eve of the Depression, publication of the Nova Scotia Reports was suspended. Nova Scotia case law continued to be recorded in a new series of reports that included judgments of courts in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

1937 – Everett Farmer hanged in Shelburne for murder, the last person executed in Nova Scotia.

1960 – Women granted the right to serve on juries.

1961 – The mandatory retirement age for Supreme Court judges was set at 75

1965 – Vincent Pottier promoted from the County Court to become the first Acadian to serve on the Supreme Court.

1966 – Creation of separate Trial and Appeal divisions, with one judge added to each court. The chief justice of the Appeal Division assumed the position of chief justice of Nova Scotia.

1967 – J. Louis Dubinsky became the first member of the Jewish community appointed to the Supreme Court.

1969 – Nova Scotia Reports resumed publication.

1971 – The Law Courts building opened on the Halifax waterfront, accommodating judges of the Trial and Appeal divisions and the County Court.

1972 – County Court judges were made local judges of the Supreme Court, enabling them to handle court business during the months when Supreme Court judges were not in the area on circuit.

1980 – Small Claims Court created to hear civil disputes involving modest amounts of money.

1982 – Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau promoted Justice Constance Glube to chief justice of the Trial Division, making her the first woman to serve as chief justice of a Canadian superior court.

1983 – Federal Justice Minister Jean Chretien refers the wrongful conviction of Mi’kmaq teenager Donald Marshall Jr., who served 11 years in prison for a 1971 murder in Sydney, to the Appeal Division for review. The court acquits Marshall and insists any miscarriage of justice is “more apparent than real” despite growing evidence of misconduct by police and prosecutors. The Nova Scotia government later establishes a royal commission to investigate the case and the province’s justice system.

1983 – Additional appointments between 1973 and 1983 brought the Supreme Court to a roster of 14 judges.

1984 – Nova Scotia became the last province to abolish the grand jury, a group of citizens empaneled at the pre-trial stage to review allegations in criminal cases.

1990 – Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall Jr. Prosecution, headed by three out-of-province judges, released a report condemning systemic racism and political influence in the Nova Scotia justice system. Reforms included giving police the power to decide whether to file criminal charges and the creation of the only Canadian prosecution agency that operates independently of government. At the request of the Nova Scotia government, the Canadian Judicial Council investigated the five Appeal Division judges who said Marshall was to blame for his wrongful conviction and, while critical of their conduct, the council found no grounds to justify their removal.

1992 – On the recommendation of the Nova Scotia Court Structure Task Force, chaired by former Dal Law School dean William Charles, the County and Supreme courts were merged to create a bench of 25 judges at the trial level. The province was divided into four judicial districts, with two Supreme Court judges residing in each one and Halifax-based judges continuing to preside over cases when on circuit. The Appeal Division was reconstituted as the Court of Appeal with eight judges.

1998 – Glube elevated to chief justice of Nova Scotia, only the second woman to be appointed chief justice in Canada.

1999 – The Supreme Court of Canada overturned the Nova Scotia courts in the case of R. v. Marshall, finding the Mi’kmaq have a right, under treaties signed in the mid-1700s, to fish to make a modest living. The ruling, which led to confrontations between licensed fishermen and natives seeking to enter the industry, came after Donald Marshall Jr. (whose wrongful conviction led to the Marshall commission) was charged with catching eels out of season.

1999 – Family Division of the court, with eight judges, established to deal with family law cases in the Halifax and Sydney areas.

2000 – Family Division of the Supreme Court starts gradually expanding its jurisdiction to other areas of the province.

2022 – All family law matters in the province are now being dealt with as per Rule 59 of the Civil Procedure Rules of Nova Scotia, essentially creating a Unified Family Court in Nova Scotia.

Introduction

Halifax was the focus for the Supreme Court in its early years, but as the population grew so did demands for trials to be held in outlying communities. In 1774 the court began holding sessions twice a year in Annapolis, Kings and Cumberland counties, and these “circuit” sittings were extended to the entire province by 1851. In newer settlements, court was sometimes held in shops, private homes, and even in the local tavern. The court’s stature and civic pride demanded better, and the nineteenth century witnessed a courthouse building boom across the province.

The result was a collection of impressive buildings, many of them still standing – monuments to the pursuit of justice. Towns vied to become the site of the county courthouse and enjoy the status and economic spinoffs they provided as litigants and witnesses converged for court business. Courtrooms echoed with cases of all kinds, from lurid murders to mundane disputes over unpaid bills. The courthouse was often the focus of community events, hosting public meetings, political rallies and serving as an enlistment centre in wartime. Many early courthouses were housed in the same building as the county jail, and it was – and remains – common for the Supreme Court to share facilities with other courts. In many areas the Province has built larger, more secure justice centres, a trend that will continue as age, building codes and increasing caseloads make some older courthouses obsolete. Several of these landmarks have already found second careers as museums.

Annapolis County – Annapolis Royal, 1837

As the birthplace of Canada’s common law system of justice, it is fitting that Annapolis Royal has a courthouse described as “expensive and magnificent” and “probably the best in the province” shortly after its completion in 1837. Adjacent to Fort Anne, it replaced a courthouse dating from 1793 that burned in 1836. The first floor, built of granite blocks, houses the jail; the stuccoed second storey, accessed via two flights of stairs meeting at the central entrance door, contains offices and the Supreme Court’s oak-paneled courtroom. Four columns frame the front door and the hipped roof is topped with a cupola added during renovations in the 1920s. It is the oldest courthouse in the province that remains in use.

Antigonish County – Antigonish, 1855

With its imposing Greek Revival columns and tall windows, the Antigonish courthouse stands as a monument to the town’s mid-nineteenth century pride and prosperity. It was too grand for some people’s tastes – a number of residents signed a petition to the legislature that complained of the “considerable sum of money” spent on the building. While the date of construction is uncertain, descendants of its builder – Antigonish contractor Alexander McDonald, known locally as “Sandy the Carpenter” – suggest it was completed in 1855. The county jail, built of stone, is attached to the rear of the building. The courthouse survived a serious fire in the 1940s and continues to be the venue for the area’s Supreme Court cases.

Argyle (District) – Tusket, 1805

The oldest surviving courthouse in Canada, Tusket’s venerable courthouse was completed in 1805 to serve an area that was in the midst of an economic boom fueled by shipbuilding, fishing and milling. A bell tower at one end of its gabled roof, directly above the main entrance, gives the building the look of a church and belies its dual role as a courthouse and jail. The building was doubled in length in 1833 and was lengthened again in 1870, but otherwise its facade has undergone few changes in two centuries.

The most famous trial held at the courthouse took place in 1922 – Omar P. Roberts was convicted of killing his housekeeper and became the last man hanged for murder in Yarmouth County. The building was used for court sessions and housed the offices of the Municipality of Argyle until 1976. Through the efforts of three local residents, the courthouse was restored and reopened in 1983 as a museum and archives.

Barrington (District) – Barrington, 1843

Barrington’s New England settlers built this courthouse as the community’s “town house” – the site of the local jail as well as a venue for town meetings and elections. When the District of Barrington was established as a separate municipal unit in 1854, the building became its courthouse. The second floor housed the courtroom, judge’s chambers, jury room and robing rooms for lawyers. It is the province’s third oldest surviving courthouse, but renovations and additions over the years have muted its formal Georgian symmetry.

Cape Breton County – Sydney

As Cape Breton’s largest urban centre, Sydney has long been the focus for court business on the island. The city’s earliest courthouse was built in 1786 and stood on North Charlotte Street. It was replaced in 1868 by a new structure on DesBarres Street. It, in turn, was replaced by a new courthouse in 1901, built near the site of the original courthouse and designed by the Hopson Brothers. This courthouse burned in 1959 and a modern, multi-storey courthouse to serve Cape Breton County was opened in 1962 on Crescent Street, overlooking Wentworth Park. Poor indoor air quality forced the closure of the courthouse in the 1990s, but it was later renovated, rechristened Silicon Island and is now home to high-tech businesses. The county’s courts are now housed in the Harbour Place development on Charlotte Street.

Colchester County – Truro, 1904

A building “more in harmony with the wealth, intelligence and public spirit of Colchester.” That was the goal of the citizens of the county and the bustling railway and factory town of Truro when they set out to build a new courthouse at the dawn of the twentieth century. By then the town’s courthouse was approaching its sixtieth year and was considered a “rather disreputable structure,” its Greek-inspired columns defaced with graffiti and its interior “shabby and not at all imposing.”

In 1903 a leading architect of the day, James Dumaresq of Halifax, was commissioned to design a new courthouse, a massive brick building trimmed in sandstone. Four stone pillars, two storeys in height, frame the main entrance to the structure, which also houses the county council chambers. A four-storey turret graces one side of the building, and a mix of windows topped with arches and keystones add interest to the facade. The large courtroom is crowned with a coved ceiling that frames a skylight of decorative leaded glass, allowing natural light to flood in. When completed in 1904, the warden of Colchester declared the building “second to none in the Province.” An addition was added in 1972 and the building remains in use by the court.

Cumberland County – Amherst, 1889

Built of red sandstone quarried within the town limits, this substantial courthouse befitted Amherst’s position as a major manufacturing centre when it was built in 1889. An arched central entrance and scalloped carvings above the tall windows combine to create an impressive facade. The second-floor courtroom is reached using a pair of elaborately carved staircases. An addition was added to the rear of the building in 1960s to provide more office space. It is the fourth courthouse to serve this county, replacing a wooden structure on the same site that burned down in 1887. It borders on a park formerly know as Court Square but renamed Victoria Square in 1887 – the year the previous courthouse was destroyed – to mark Queen Victoria’s fiftieth year on the throne.

Digby County – Digby, 1910

The fire that destroyed the Annapolis Royal courthouse in 1836 provided an opportunity for the residents of western Annapolis County to demand their own municipality – with its own courthouse and registry offices. Digby County was duly established in 1837 and the town of Digby was chosen over Weymouth, a port further to the west, as the site of the courthouse. The original Georgian-style structure was considered inadequate by the turn of the century and a larger brick structure was erected on the same site and completed in 1910. It features castle-like rounded turrets, topped with a conical roof, at each corner. Prominent architect Leslie Fairn, fresh from designing the King’s County courthouse in Kentville, drew up the plans. The building also housed the county council chambers and the courtroom features a two-tier public gallery and the scales of justice carved into a wood panel above the judge’s bench.

Guysborough County – Guysborough, 1843

Even though it dates to 1843, the Guysborough courthouse is the third to serve a county founded by disbanded British soldiers after the American Revolution. The first courthouse, which also housed the jail, was built in 1790 and a replacement was completed in 1825. It was replaced, in turn, by a simple, one-storey courthouse with a gabled roof and windows featuring Gothic arches reminiscent of a church. A separate jail building was erected next door. When court was not in session, the building hosted municipal council meetings and rallies and housed exhibits for agricultural fairs held on its grounds. Court sittings moved to the town’s new municipal building in 1973 and the courthouse is now a museum.

Halifax County – Halifax, 1860

The Supreme Court convened for the first time in 1754 in a building at the corner of Argyle and Buckingham Streets, now the site of the Scotia Square office towers. After this building burned down in July 1789, court was held for a time in a large room at the Golden Ball tavern. Space was then leased from a local merchant – a “low, dark” upstairs room in a warehouse located on the site now occupied by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. A new County Courthouse was built for the lower courts about 1810, adjacent to the city’s open-air market on George Street, but the Supreme Court was destined for grander surroundings. Upon the completion in 1818 of Province House, the fine sandstone building on Hollis Street that houses the Legislature and its offices, the Supreme Court moved into the second-floor chamber now used as the Legislative Library.

By the 1850s a decision was made to consolidate all the courts under one roof. After fires razed many downtown buildings during that decade, officials abandoned plans for a wooden structure in favour of a more fireproof one made of stone, to protect the legal records it would house. A Toronto-based architect, William Thomas, was retained and created a palatial structure in sandstone, replete with carvings of the faces of snarling lions and stern, bearded men. A temple-like projection from the facade dwarfs the entrance doors and those who enter – a fitting image to convey the power and majesty of the courts. After its completion in 1860, a city directory gushed that the building “cannot be surpassed for architectural beauty by any city of the same size on the continent of America.”

Located near the foot of Spring Garden Road, the building initially housed two courtrooms. An addition to the back in the 1880s added a third. Matching wings were erected on either end of the building in 1908 and 1930 to add additional courtroom and office space. The courthouse suffered $19,000 in damage in the 1917 Halifax Explosion, even though it was far removed from the site of the blast. Its courtrooms have been described as the “most flamboyantly decorated” of any in the province, rich in fine woodwork and plaster details. One of the courtrooms even featured an elevator that could ferry prisoners directly into the courtroom from the cells below, but it was removed in the 1930s after is malfunctioned and left a prisoner trapped between floors.

After a modern Law Courts complex for Halifax County was built on the waterfront in 1971, the old courthouse (designated a national historic site in 1969) was transformed into a provincial government library. The seven-storey Law Courts provided eleven courtrooms – enough for the Supreme Court and its newly created Appeal Division, as well as the County and Provincial courts. By the 1980s, however, more judges and support staff were needed to deal with an increasing caseload and the building proved too small to accommodate all levels of court. The Provincial Court returned to the refurbished Spring Garden Road courthouse in 1985.

Hants County – Windsor 1950

Hants County is divided into two smaller municipalities, East and West Hants. The largest town in West Hants, Windsor, emerged as an important commercial and railway centre and was home to King’s College, the province’s first institution of higher learning, until it was relocated to Halifax in the 1920s after a disastrous fire. Windsor was among the first communities outside Halifax to host Supreme Court sittings after the circuit system was established in 1774.

A courthouse was built on the present-day site of Christ Church in 1804, and was followed by a succession of court buildings at the corner of King and Victoria streets. The courthouse erected in 1897 was an elegant, two-storey brick building, with a hipped roof and large domed windows. It burned in December 1946 and the current courthouse was built at the same corner in 1950, with chief Justice J.L. Ilsley laying the cornerstone. Charles Killinbeck of Kentville produced the functional design, which is far less ornate than its predecessor, and the building also housed the county jail and its 17 cells. Court sittings have been transferred to the regional justice centre in Kentville.

East Hants had its own courthouse as early as the 1860s. It was built in Gore, a small farming community where antimony – a metal used to strengthen lead – was mined for export to Wales from the 1880s until 1917. The courthouse stood for 90 years on a site known locally as ‘Judgment Hill,’ but it was no longer in use for court sessions when it was destroyed by fire in 1956.

Inverness County – Port Hood 1936

In 1824, shortly after Cape Breton was annexed to mainland Nova Scotia, the island was divided into judicial districts and Port Hood, on the western coast, was proclaimed the site where the “Courts of Common Pleas and Session of the Peace shall hereinafter be held.” With its large harbour and thriving fishing industry, Port Hood was a natural choice as shiretown (the seat of local government) when Inverness County was established in 1837.

The community has had a succession of courthouses, all located on the aptly named Court House Square. The first was a small stone structure built sometime after 1825. It was replaced in 1872 by a building that boasted a large courtroom with galleries ringing the rear and side walls, giving spectators prime seats for viewing the proceedings. This courthouse was destroyed by fire in December 1935, along with many of the court records it contained. The current courthouse was completed in 1936 and renovated in the 1940s. A major extension was added to the north end of the building in 1967 to provide additional office space.

King’s County – Kentville, 1903

Kentville replaced Wolfville as the administrative centre for King’s County in the 1780s, and a combination courthouse and jail was built in 1829. It was destroyed by fire 20 year later but the replacement courthouse was considered “scandalously inefficient” and “an eyesore to the community” by the turn of the century. A leading Maritime architect, Leslie A. Fairn, was commissioned to design a new courthouse on Cornwallis Street in 1903.

Built of brick and topped with a cupola and weather vane, the building housed county offices on the ground floor and the Supreme Court chamber on the floor above. The courtroom is ornate, with stained walnut paneling and the scales of justice carved in wood above the judge’s bench – reputedly the work of a local inmate. According to one observer, major trials would prompt men from all over the county to converge on Kentville and “all day remain spell-bound in the stifling courtroom, listening to the evidence as the various witnesses were called.” A modern Law Courts, part of a new municipal building, opened on the same street in 1980 and the old courthouse is now the King’s Historical Society Museum.

Lunenburg County – Lunenburg, 1892; Bridgewater, 1893

Courthouses and municipal offices bring jobs, economic spinoffs and prestige to their host communities. Towns would sometimes vie for the honour of being the “shiretown” or county seat, and in Lunenburg County this rivalry led to the construction of two courthouses. Lunenburg, founded in 1754 and only the second Nova Scotia settlement established under British rule, erected a courthouse in 1775. When a replacement was needed in the late 1800s officials in the bustling lumber town of Bridgewater also claimed the right to host the new courthouse. After three years of debate and legal actions, courthouses were built in both communities.

The Lunenburg courthouse, completed first in 1892, is a towering building of brick and stone designed in the Second Empire style that features a mansard roof and entrances that project from the centre of the facade. Bridgewater followed a year later with large wooden structure in the same architectural style, with a central tower rising over the main entrance. Both buildings provided courtrooms, judge’s chambers and jury rooms. The county council, saddled with the expense of maintaining duplicate facilities, agreed to hold its meetings at both buildings on an alternating basis.

Pictou County – Pictou, 1856

After its creation as a separate district in 1790, Pictou was in desperate need of a courthouse. The first sittings of the Supreme Court were reportedly held in a barn that also housed a pig sty and, in summer, jurors retired to a nearby pasture to consider their verdicts. A courthouse and jail building was erected in 1813. The prosperity of the county’s coalfields and factories led to the construction in the 1850s of an ornate two-storey building decorated with exterior architectural flourishes and intricate wood carving and mouldings inside.

The impressive Supreme Court chamber was two stories high, with a spectators’ gallery and a stained glass window depicting the goddess of justice with her sword and scales. A federal government heritage report described it as “the most elaborately detailed courthouse constructed of wood in Nova Scotia.” Sadly, the building fell victim to arson and burned to the ground in 1985. By then court sessions were held in a new facility, the Pictou Justice Centre, built on the town’s waterfront in the 1970s.

Queen’s County – Liverpool, 1854

With its classic architecture, the Queens County courthouse in Liverpool would be at home among the temples of ancient Greece. A large portico, spanning the entire width of the front facade, is supported by four massive, fluted columns. The impressive wooden building was erected in 1854 to replace a predecessor that visiting Supreme Court judges condemned as “truly disgraceful.” The new building, in contrast, was praised in the local newspaper as “very comfortable, substantial and well built.” It is also compact, consisting of an entry hall, courtroom and rooms for the judge and lawyers laid out on a single floor. A dispute among local officials over where it should be sited within the town continued even after its completion – one of the first cases heard within its walls dealt with an attempt to withhold payment to the builder. Built the year the Supreme Court marked its centennial, it remains in use.

Richmond County – Arichat, 1847

The port of Arichat, on Cape Breton’s southern coast, was one of the province’s busiest ports – hailed as “the key to the Canadas” due to its strategic location at the entrance to the Strait of Canso – when its impressive courthouse was erected in 1847. The designer of this “ornament to the County of Richmond,” as local officials described it, was Alexander McDonald, who went on to build courthouses with nearly identical Greek-inspired facades in Sherbrooke and Antigonish. Besides housing the jail, Supreme Court chamber and offices, the courthouse was the heart community life from its inception until the early 1900s, hosting election debates, gala balls and even traveling vaudeville shows. A rear addition was built in 1978 to house municipal and court offices and the courtroom remains in use.

Shelburne County – Shelburne – 1903

After this South Shore town was founded by Loyalists in 1784, court was held in a rented house near the centre of the community. Archival records show a permanent courthouse was built about 1849 at the corner of King and Mowat streets. The current courthouse, a three-storey, wood-frame structure, was built in 1902-03 and designed by Halifax architect Harris S. Tremaine. A two-storey brick addition was completed in the 1960s. The building houses a courtroom, municipal and court offices, the sheriff’s department and a jail.

The courthouse was the scene of Nova Scotia’s last execution. In December 1937, Everett Farmer of Shelburne was hanged for the murder of his half-brother. A makeshift gallows was built in a room on the building’s second floor that was so small, it could barely accommodate the executioner and the half-dozen witnesses (the practice of holding public executions ended in the mid-1800s). A large beam was erected across the ceiling of the room to support the noose, which dangled over a hole cut in the floor. When a trapdoor covering the hole was sprung, the condemned man’s body dropped through and into the room below, breaking his neck.

St. Mary’s (District) – Sherbrooke, 1858

In 1841, within a year of the District of St. Mary’s being carved out of neighbouring Guysborough County, a courthouse was built at its most important village, Sherbrooke. Almost immediately, local officials began raising money and making plans for a more elaborate structure. The builder, Alexander McDonald, copied the Greek Revival plan he had used in his earlier courthouses in Antigonish and Arichat, with four temple-style columns to frame the main entrance. The courthouse was used for an array of public meetings and lectures over the years, but officials rejected a bid to use it for a dance school.

Named in 1815 in honour of Sir John Sherbrooke, Nova Scotia’s lieutenant governor, the settlement became a boom town after gold was discovered in the area in the 1860s. Little changed since the gold rush ended in the late 1800s, the community found new life in 1969 as the province’s largest museum. More than 25 of its historic homes, shops and public buildings have been preserved as they were a century ago and are open to the public. Among them is the courthouse, was continued to be used for court sessions until July 2000. With its excellent acoustics, the courthouse has found new life as a venue for concerts and theatrical performances.

Victoria County – Baddeck, 1890

Victoria County was created in 1851 but managed to soldier on without a courthouse for almost four decades. A jail was built in 1852 at Baddeck, the county seat, but court sessions apparently were held in the home of the local magistrate. The jail was demolished and replaced in 1890 with the courthouse that still stands on the site. The granite-block first storey housed the jail and offices, with an oak staircase leading to the Supreme Court chamber on the second floor. The second storey was built of wood, with large windows overlooking the Bras d’Or Lakes. A wing to house additional court and municipal offices was added in 1967, matching the original architecture. A further expansion was completed in 1980.

Yarmouth County – Yarmouth, 1933

Yarmouth, the largest community in southwestern Nova Scotia, was a major centre for trade, fishing, shipbuilding and manufacturing in the nineteenth century. The community’s first courthouse was built in 1820, but two of its three replacements succumbed to fire. The courthouse built in 1863 burned down in 1921. A new one was erected, only to be destroyed by fire a decade later. The current courthouse was opened in 1933 and survived a 1988 fire. A two-storey structure built of brick, its functional exterior incorporates traditional Georgian features and symmetry that produce a blend of the old and the new.

----

Sources: C.A. Hale, The Early Court Houses of Nova Scotia, vols. 1 and 2, Manuscript Report No. 293, (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1977); Hale, “Early Court Houses of the Maritime Provinces,” in Margaret Carter, comp., Early Canadian Court Houses (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1983), pp. 37-77; South Shore, Seasoned Timbers, vol. 2: Some Historic Buildings from Nova Scotia’s South Shore (Halifax: Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia, 1974); Master Plan for Nova Scotia Courthouse Facilities, prepared for Departments of Justice and Transportation and Public Works, March 31, 1997; Dean Jobb, Shades of Justice: Seven Nova Scotia Murder Cases (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 1988).

Introduction

Twenty-one chief justices have presided over the Nova Scotia Supreme Court in the 250 years since English lawyer Jonathan Belcher arrived in Halifax to found the court in October 1754. The longest serving chief justice, Sampson Salter Blowers, was in office for a remarkable 35 years, from 1797 until he retired in 1832 at age 90. Lauchlin Daniel Currie, in contrast, served barely 13 months before retiring in 1968. Two of their number – Charles Morris and Isaac Deschamps – had no legal training and held office on an interim basis during the court’s formative years. While the rest were lawyers, and most made their mark in politics, they came from varying backgrounds – one worked as a coal miner and bricklayer, one served in the military, one was Halifax’s mayor and another its city manager. A couple of chief justices turned their hand to writing, chronicling the court’s history and the careers of their predecessors. Our current chief justice, Constance R. Glube – the only woman to hold the post – will retire at the end of 2004, making way for her successor as Nova Scotia’s twenty-second chief justice.

Jonathan Belcher 1754-1776, First Chief Justice

After Halifax was founded in 1749, Nova Scotia’s fledgling justice system was in the hands of magistrates and members of the governor’s council – none of them legally trained. Demands for a trained law officer were answered in 1754, when British officials dispatched Jonathan Belcher to the colony as chief justice of a newly created Supreme Court. Born in Boston on July 23, 1710, Belcher was the son of a New England governor and well educated, with degrees from Harvard College and Cambridge University. He studied law in London, was admitted to the English bar in 1734, practiced law in Dublin and published a compilation of Irish law.

Installed as chief justice in October 1754 in an elaborate ceremony in Halifax, Belcher applied English laws and precedents to offset the influence of the Massachusetts laws previously favoured within the colony. Belcher drafted many of Nova Scotia’s earliest statutes and laid the legal foundations for Canada’s first elected legislature, which convened in 1758. He assumed the governor’s duties upon the death of Charles Lawrence in 1760, but political inexperience and clashes with Halifax’s merchants ensured he was the only chief justice to govern Nova Scotia. His legal opinion supporting the expulsion of the Acadians in 1755 and his attempt to deport a group of Acadian prisoners amid fears of a French attack in 1762 further tarnished his reputation. Belcher sought permission to resign in 1776 due to declining health and died March 30, 1776 in Halifax.

For more information on Jonathan Belcher, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=35872

Charles Morris 1776-1778, Second Chief Justice

Born June 8, 1711 in Boston, Charles Morris first came to Nova Scotia as an officer in New England regiments sent to bolster the British garrison at Annapolis Royal. His skill at cataloguing the areas he visited led to his appointment as Nova Scotia’s first surveyor. Morris laid out the street plans for Halifax and Lunenburg and surveyed outlying townships as far north as New Brunswick as the colony grew in the 1760s.

Although he lacked formal legal training, Morris was made a justice of Halifax’s inferior court of common pleas in 1752. In 1763 he was one of two assistant judges appointed to the Supreme Court to assist the chief justice, Jonathan Belcher. When Belcher died in March 1776, Morris, as the senior assistant judge, was tapped to fill in as chief justice until a replacement was found. As chief justice Morris heard a number of major cases, including charges of treason against rebel soldiers who besieged Fort Cumberland, near Amherst, in 1776, in a failed effort to import the American Revolution to Nova Scotia. He reverted to his assistant judge’s post in May 1778 when Bryan Finucane – who had been appointed chief justice at the end of 1776 – finally took office. Morris died in Windsor, N.S. on Nov. 4, 1781.

For more information on Charles Morris, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=36201

Bryan Finucane 1778-1785, Third Chief Justice

Bryan Finucane was born in County Clare – the only Irish-born chief justice of Nova Scotia – sometime before 1744. He studied law at London’s Middle Temple, was admitted the Irish bar in 1764 and practiced in Dublin for several years. Finucane was appointed chief justice in December 1776 but did not arrive in Halifax until April 1778. He was sworn into office on May 1, 1778.

Finucane balked at traveling on circuit and tried, unsuccessfully, to reduce the length of sittings in Halifax. He was granted a leave absence to travel to England, where he spent most of 1782-1783. Upon his return he was sent to New Brunswick to help settle the claims of Loyalist refugees. Considered a man of great integrity and an “upright judge,” Finucane died in Halifax on August 3, 1785 after “a painful and tedious illness.” He is buried at St. Paul’s Church in Halifax.

For more information on Bryan Finucane, see Barry Cahill, “The Career of Chief Justice Bryan Finucane,” Nova Scotia Historical Society Collections, vol. 42 (1986), pp. 153-69.

Isaac Deschamps 1785-1788, Fourth Chief Justice

Isaac Deschamps is believed to have been born in Switzerland in 1722 and came to Halifax in 1749, the year the city was founded. Fluent in French and English, he was a natural choice as an agent for merchants trading with the Acadians and Mi’kmaq and was often called upon to translate official documents. Between 1759 and 1783 he served as MLA for a succession of ridings – Annapolis County, Falmouth Township and Newport Township.

In 1761 he was appointed justice of the inferior court of common pleas and judge of probate for King’s County. He served as a judge of the inferior court of Prince Edward Island in 1768, but the appointment was cut short when the island became a separate colony in 1769. He was named an assistant judge of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court in 1770. Deschamps had no legal training and in 1787 some politicians and lawyers, including Loyalists who coveted judgeships for themselves, accused Deschamps and assistant judge James Brenton of incompetence and bias. The controversy over the “Judges’ Affair” continued even after English lawyer Jeremy Pemberton replaced Deschamps as chief justice in 1788. The legislature voted to impeach Deschamps and Brenton in 1790 but the British authorities ultimately exonerated both judges. Deschamps continued to serve as a judge until his death at Windsor, N.S., on August 11, 1801.

For more information on Isaac Deschamps, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=36488

Jeremy Pemberton 1788-89, Fifth Chief Justice

Jeremy Pemberton was the youngest chief justice of the Supreme Court, taking office at age 33. Born in Cambridgeshire, England in 1741, he was the grandson of Sir Francis Pemberton, a lord chief justice of England. He attended Lincoln’s Inn and was admitted to law practice in 1762.

In 1785 he was appointed to investigate claims of Loyalists in the British North American colonies. He was named chief justice in August 1788 in the midst of the “Judges’ Affair,” as Loyalist newcomers agitated to impeach the Supreme Court’s two assistant judges – neither of them legally trained – on allegations of incompetence and bias. While Pemberton provided the legal expertise the court needed, he did not stay long enough to stabilize the court. He resigned in October 1789 and returned to England, where he died on July 14, 1790.

For more information, see Sir Joseph A. Chisholm, “Three Chief Justices of Nova Scotia,” Nova Scotia Historical Society Collections, vol. 28 (1949), pp. 148-58.

Sir Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange 1789-1797, Sixth Chief Justice

Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange had been practicing law in England for just four years when he was named chief justice in 1789 and sent to Nova Scotia to rescue the court from the taint of the “Judges’ Affair.” Born in England on November 30, 1756, Strange obtained degrees from an Oxford college and trained at Lincoln’s Inn before being admitted to the bar in 1785. He had a reputation as “a most excellent theoretical lawyer.”

Strange managed to mollify those seeking to impeach assistant judges Isaac Deschamps and James Brenton, whom he considered “very amiable, deserving persons and of great assistance” to him. Governor John Wentworth praised Strange as “indefatigable in his duty” and said losing him would be “the greatest misfortune” to Nova Scotia. But Strange was soon ready to move on and, as early as 1794, was lobbying for the chief justiceship of Upper Canada. He returned to England in 1796 and resigned the following year. He became chief justice of the supreme court in Madras (India) in 1800 and wrote a two-volume text on Hindu law. He died July 16, 1841 in England.

For more information on Sir Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=37801

Sampson Salter Blowers 1797-1832, Seventh Chief Justice

One of Sampson Salter Blowers’ first cases was helping to defend British Redcoats accused of murder in 1770 for firing into crowds in the infamous Boston Massacre. Not surprisingly, the Harvard-educated lawyer was among the Loyalists forced to flee to Nova Scotia after the American Revolution. Born in Boston on March 10, 1741 (possibly 1742), Blowers was called to the bar in Massachusetts in 1766. Imprisoned briefly by the American authorities, Blowers was an admiralty judge in British-occupied Newport, R.I. and later New York’s solicitor general.

He arrived in Halifax in 1783, carved out a busy law practice and was named the province’s attorney general a year later. He was elected as an MLA for Halifax County in 1785 and selected as speaker of the House of Assembly. Blowers backed the Supreme Court’s beleaguered assistant judges Isaac Deschamps and James Brenton in the “Judges’ Affair” and joined them on the bench in September 1797, when he was appointed chief justice. One contemporary considered him “truly eminent for a high standard of legal knowledge, logical skill, and power of argument.” Even though advancing age curtailed his ability to conduct trials, Blowers clung to office but was finally forced to resign in late 1832. He died on October 25, 1842 in Halifax, seven months after his 100th birthday, after breaking his hip in a fall.

For more information on Sampson Salter Blowers, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=37377

Sir Brenton Halliburton 1833-1860, Eighth Chief Justice

Brenton Halliburton is the only chief justice who commanded a fortress as well as the Supreme Court. Born December 27, 1774, in Newport, R.I., he came to Halifax in 1782 when his father, a doctor in the Royal Navy, joined the Loyalist exodus. Halliburton was educated in London but returned to Nova Scotia and joined the army when war broke out with France in 1793. He was put in command of York Redoubt, a fortress that guarded the entrance to Halifax Harbour.

Halliburton, who had begun studying law before the war began, resumed his legal career and was admitted to the bar in 1803. When his uncle, James Brenton, died in January 1807, Halliburton took his place as an assistant judge of the Supreme Court – becoming the first assistant judge with legal training. The governor of the day, Lord Dalhousie, regarded Halliburton as “a loyal subject and a morally good man.” Halifax lawyer Peter Lynch would later observe that Halliburton’s legal knowledge “was not very extensive, but like his wine it was of the best quality.”

Halliburton would later claim he shouldered the chief justice’s duties for the last decade of

Sampson Salter Blowers’ long tenure. When the aging Blowers was finally forced to retire, Halliburton succeed him in 1833. He presided over Joseph Howe’s libel trial in 1835 and was the last chief justice to sit as a member of the council that governed the province. He died in office on July 16, 1860, at age 85.

For more information on Sir Brenton Halliburton, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=38071

Sir William Young 1860-1881, Ninth Chief Justice

Born in Falkirk, Scotland, on September 8, 1799, William Young claimed to have completed a degree from the University of Glasgow by age 14, when he came to Halifax with his family. His father was John Young, a merchant and politician who wrote the “Letters of Agricola,” a popular newspaper series promoting agriculture. After working as a trading agent for his father, William Young was called to the bar in 1825. In the courtroom, he was described as “an excellent tactician (who) pressed himself strongly on courts and juries.”

Young followed his father into provincial politics, winning the Cape Breton riding of Inverness in 1836. He became speaker of the House of Assembly and was allied with Joseph Howe and other reformers in the drive for Responsible Government in the 1840s. Young served as attorney general from 1854-1857 and became premier in February 1860. Young had long coveted the chief justiceship and, after Brenton Haliburton’s death later that year, he outraged his political rivals by naming himself to the post.

His judicial rulings were considered “showy rather than substantial.” Short of stature – he bore the nickname “Little Billy” all his life – Young reputedly padded his courtroom chair with cushions to ensure he sat no lower than his fellow judges. Young was a generous benefactor of Dalhousie University and the City of Halifax – he convinced the British government to lease Point Pleasant Park to the city and donated the gates that adorn the park’s entrance. Young retired in 1881 and died on May 8, 1887.

For more information on Sir William Young, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=40041

James McDonald 1881-1905, Tenth Chief Justice

Born in Bridgeville, N.S., on July 1, 1828 and a descendant of Pictou County’s Scottish settlers, James McDonald taught school for a couple of years before studying law with a local legal and political luminary, Martin I. Wilkins. Called to the bar in 1851, McDonald practised law in Pictou and had a commanding presence in the courtroom, arguing cases “with considerable skill and fluency.” Elected MLA in 1859, he was appointed chief railway commissioner in the Tory government and fought to have a branch line built to his rapidly industrializing Pictou county riding. McDonald supported Confederation and was elected as a Conservative MP for Pictou County in 1872 and 1878.

He became federal minister of justice in 1878 and held the post until he was named chief justice in May 1881 – a rare case of a lawyer being appointed directly to the chief justice’s post. Just 52, he injected “energy, affability and courtesy” into an aging bench in need of leadership and fresh blood. McDonald declined the knighthood that, by tradition, came with the position. While known for not keeping abreast of changes to the law, he often championed the underdog and “would strain the law to the breaking-point to save someone.” Fluent in Gaelic, he once presided over a trial at Baddeck in which he and everyone else involved – lawyers, witnesses and jurors – used only that language. McDonald retired in 1904 and died Oct. 3, 1912, at Blinkbonnie, his Halifax estate.

For more information on James McDonald, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=41701

Sir Robert Linton Weatherbe 1905-1907, Eleventh Chief Justice

Born in Bedeque, P.E.I. on April 7, 1836, Robert Linton Weatherbe was the son of a merchant and shipowner. He received a master of arts degree from Acadia College in 1861 and was admitted to the Nova Scotia bar two years later. Weatherbe practiced in Halifax with Wallace Nesbit Graham, the thirteenth chief justice, and was the Legislature's law clerk from 1868-1878. Known for his "florid eloquence and impassioned rhetoric," he helped Canada win a major fishing dispute with the United States in 1877.

He was named to the Supreme Court in October of the following year, one of many last-minute Liberal appointees rewarded before the defeated government of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie left office. Described as "impatient, vain, and domineering," Weatherbe became something of a devil's advocate on the court, frequently writing judgments that dissented from the views of his colleagues. As senior judge, he was tapped in January 1905 to replace James McDonald as chief justice, only to retire little more than two years later in March 1907. Weatherbe died in Halifax on April 27, 1915.

For more information on Sir Robert Linton Weatherbe, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=41883

Sir Charles James Townshend 1907-1915, Twelfth Chief Justice

Charles James Townshend was born in Amherst, N.S. on March 22, 1844, the son of a clergyman and grandson of a Supreme Court judge, Alexander Stewart. He graduated from King’s College in Windsor, N.S. with honours in 1863. Townshend articled in the law office of Senator R.B. Dickey of Amherst. He was admitted to the bar in 1866 and eventually took over the practice when Dickey retired. He served as MLA for Cumberland County from 1878-1884, was minister without portfolio in the provincial cabinet until 1882, then switched to the federal arena in 1884. In 1885, as Cumberland’s MP, Townshend put forward an amendment to the Franchise Bill to delete a clause that would have given women the right to vote.

Townshend was appointed to the Supreme Court in March 1887 and, in 1907, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier appointed him chief justice. Sir Henry Strong, chief justice of Canada, once noted that Townshend’s rulings were “characterized by lucidity and sound reasoning.” Another observer noted that his reasoned judgments and “modest demeanor ... placed him beyond criticism by members of the bar.” Townshend, who published studies of other chief justices and court history, retired in April 1914. He died in Wolfville on June 16, 1924.

For more information on Sir Charles James Townshend, see W. Stewart Wallace, The Macmillan Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Toronto: Macmillan, 1973), p. 753.

Sir Wallace Nesbit Graham 1915-1917, Thirteenth Chief Justice

Political and professional ties propelled Wallace Graham to the chief justice’s post, but his impartiality and legal skill cemented his claim to the office. Born in Antigonish on January 15, 1848, he was the son of a sea captain and shipbuilder. Educated at Acadia College, he studied law with a Halifax firm and was called to the bar in 1871. Graham practiced in Halifax with future Conservative prime ministers John S.D. Thompson and Robert L. Borden, and was also a law partner of the eleventh chief justice, Sir Robert Linton Weatherbe.

Colleagues respected Graham’s “character, integrity, and ability,” according to a biographer. Thompson considered him the ablest lawyer in the Maritimes and, as federal minister of justice, appointed Graham to the Supreme Court in September 1889. Graham accepted out of a desire to improve and professionalize the court. His rulings in divorce and child custody cases have been credited with making the law more fair to women. His reputation for impartiality led to his 1914 appointment to chair a royal commission that investigated politically sensitive conflict-of-interest allegations against Nova Scotia’s attorney general. In April 19, 1915 Borden, by now prime minister, named him chief justice and Graham was knighted the following year. He died in office on October 12, 1917.

For more information on Sir Wallace Nesbit Graham, consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online: http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=37377

Robert Edward Harris 1918-1931, Fourteenth Chief Justice

Robert Edward Harris was born at Annapolis Royal, N.S. on August 18, 1860. He taught school in nearby Tupperville for two years, then studied law with a local lawyer and in the firm of Sir John S.D. Thompson, later the prime minister, and Sir Wallace Graham, who would become his predecessor as chief justice. Harris was admitted to the Nova Scotia bar in 1882 after placing first in the bar exams. While practicing law in Yarmouth and later in Halifax, Harris was described as “an organizing genius” and the “most courteous of men.” A specialist in corporate law, he was president of Eastern Trust Company, Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company and other firms. He served as president of the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society in 1906 and in 1908-1909.

Harris was a friend of Prime Minister Robert L. Borden, who appointed him to the Supreme Court in June 1915 and bypassed senior judges to name him chief justice in March 1918. Harris, regarded as “an efficient chief justice,” collected many of the portraits of former chief justices and senior judges that now hang in The Law Courts in Halifax and were reproduced in a book compiled by his nephew, R.V. Harris. Another of his legacies was the ceremonial mace he presented to the Nova Scotia Legislature. Harris died on May 30, 1931.

For more information on Robert Edward Harris, see R.E. Inglis, “Sketches of Two Chief Justices of Nova Scotia, Sir Charles Townshend, Robert E. Harris,” Nova Scotia Historical Society Collections, vol. 39 (1977), pp. 107-19.

Sir Joseph Andrew Chisholm 1931-1950, Fifteenth Chief Justice

Joseph Andrew Chisholm was born in St. Andrews, N.S., on January 9, 1863 and educated at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish and at Dalhousie Law School. Called to the bar in 1886, he joined the Halifax law firm headed by a future prime minister, Robert L. Borden. Chisholm was mayor of Halifax from 1909-1911 and in 1916 Borden’s government appointed him to the Supreme Court.

Chisholm was elevated to the chief justiceship in 1931. A keen student of the province’s legal history, he wrote a number of historical papers on the careers of his predecessors as chief justice and edited a revised edition of The Speeches and Public Letters of Joseph Howe that was published in 1909. The first Dalhousie law graduate to serve on the court, Chisholm was also the last Nova Scotia chief justice to be knighted, an honour bestowed in 1935. He remained chief justice until his death on January 22, 1950 at age 87.

For more information on Sir Joseph Andrew Chisholm, see W. Stewart Wallace, The Macmillan Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Toronto: Macmillan, 1973), p. 136.

James Lorimer Ilsley 1950-1967, Sixteenth Chief Justice

James Lorimer Ilsley, better known as J.L. Ilsley, was born in Somerset, N.S. in 1894. He attended public schools in Berwick and went on to Acadia University and Dalhousie Law School. He was admitted to the bar in 1916 and practiced in Kentville for 20 years. In 1926, he embarked on a remarkable public career during which he was elected five times as MP for an Annapolis Valley riding. From 1935-1940 he was minister of national revenue and served as the minister of finance for the remainder of the Second World War. Historian Jack Granatstein has described him as possessing “the sharpest mind and the finest oratorical style” of Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s talented wartime cabinet.

Ilsley was known as a “champion of world co-operation” and was Canada’s delegate to the League of Nations and in 1947 to the United Nations. He was federal justice minister and attorney General from 1946 to 1948. Appointed to the Supreme Court in May 1949, he was named chief justice less than a year later. In 1966, he became chief justice of the court’s newly created Appeal Division. He died on January 14, 1967.

Lauchlin Daniel Currie 1967-1968, Seventeenth Chief Justice

Born March 28, 1893 at North Sydney, Lauchlin Daniel Currie worked as a coal miner and bricklayer before graduating from Dalhousie Law School in 1922. He was the lawyer for the Cape Breton division of the United Mine Workers of America for a decade, before entering politics in 1933.

Currie was Liberal MLA for Cape Breton East from 1933-1941 and represented another Cape Breton riding, Richmond, from 1941-1949. During the 1940s he held a number of cabinet posts, including attorney general and minister of mines, labour and public health. Appointed to the Supreme Court in 1949, he was elevated to chief justice of the Trial Division in 1966 and to chief justice of the Appeal Division (making him chief justice of Nova Scotia) in February 1967. He retired in March 1968 and died the following February in Halifax.

For more information, see Shirley B. Elliott, ed., The Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia, 1758-1983: A Biographical Directory (Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia, 1984), p. 45.

Alexander Hugh MacKinnon 1968-1973, Eighteenth Chief Justice

Alexander Hugh McKinnon was born in Inverness, N.S., on December 24, 1904 and educated at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish. He received his law degree from Dalhousie Law School in 1929 and was admitted to the bar that year. He practiced law for twenty years in Inverness, a coal mining town on Cape Breton’s west coast. The MLA for Inverness from 1940-1953, he served as minister of health and as minister of labour and mines.

In 1954 McKinnon was appointed judge of the County Court for Antigonish. He was appointed a judge of the Supreme Court’s Appeal Division in 1966 and, in 1968, he was named chief justice of Nova Scotia. He died on June 16, 1973.

For more information, see Shirley B. Elliott, ed., The Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia, 1758-1983: A Biographical Directory (Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia, 1984), p. 140.

Ian Malcolm MacKeigan 1973-1985, Nineteenth Chief Justice

Ian Malcolm MacKeigan had no previous judicial experience when he was appointed chief justice – the first Nova Scotia lawyer named chief justice “off the street” since James McDonald in 1881. Born in 1915 in Saint John, N.B., MacKeigan graduated from Dalhousie Law School and was admitted to the Nova Scotia bar in 1938. After working in Ottawa for the federal government for a decade, he returned to Halifax, where he practiced law from 1950-1973. He chaired the Atlantic Development Board, was a member of the Economic Council of Canada, and served as a director of major companies including John Labatt Ltd. and Gulf Oil Canada. He was president of the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society from 1959-1960.

His tenure was marred by a case that began before he assumed office in 1973 – Donald Marshall Jr.’s wrongful murder conviction in 1971. When the case was brought before the Appeal Division in 1982, MacKeigan and four other judges cleared Marshall of the crime but, in effect, blamed him for the miscarriage of justice. The inquiry into the Marshall case tried to force the judges to explain themselves and later criticized the court’s effort to exonerate the justice system. In 1985, in the midst of the Marshall controversy, MacKeigan stepped down as chief justice but continued to hear cases as a supernumerary (part-time) judge until 1990. He died May 1, 1996, in Halifax.

For more information on Ian Malcolm MacKeigan, see K. Simpson, ed., Canadian Who’s Who, vol. 27 (1992) (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), p. 659.

Lorne O. Clarke 1985-1998, Twentieth Chief Justice

Born in Malagash, N.S. in 1928, Lorne Clarke received his legal education at Dalhousie and Harvard universities. He taught at Dalhousie Law School in the 1950s, practiced law in Truro from 1959-1981, served on two royal commissions that examined workers' compensation, and was often called upon to settle labour and commercial disputes.

Born in Malagash, N.S. in 1928, Lorne Clarke received his legal education at Dalhousie and Harvard universities. He taught at Dalhousie Law School in the 1950s, practiced law in Truro from 1959-1981, served on two royal commissions that examined workers' compensation, and was often called upon to settle labour and commercial disputes.

Clarke was appointed to the Supreme Court's Trial Division in February 1981 and was elevated to chief justice of the Appeal Division (now the Court of Appeal) in 1985. He instituted many reforms in response to the 1990 inquiry into Donald Marshall Jr.'s wrongful conviction for murder, which found that racism and favouritism tainted the province's justice system. Clarke is credited with making Nova Scotia's courts a national leader in judicial education and media relations, as well as more accessible and accountable to the public.

Clarke retired from the court in June 1998 and joined a group of retired judges and senior lawyers at ADR Chambers, which offers mediation services. He continues to contribute to the community in a variety of ways, including as chair of a committee that selected a memorial to the victims of the 1998 crash of Swissair Flight 111 off Peggy's Cove.

For more information on Lorne O. Clarke, see the biography on the ADR Cambers website: http://www.adrchambers.com/cv-clarke.htm

Constance R. Glube 1998-2004, Twenty-first Chief Justice

Constance R. Glube led the Supreme Court into the twenty-first century. She was born in Ottawa on November 23, 1931, and received her undergraduate education at Montreal’s McGill University. She completed her law degree at Dalhousie Law School in 1955 and was admitted to the bar the following year. She practiced in Halifax for four years before joining the legal department of the City of Halifax in 1969. A series of firsts followed – the first woman to be a city manager in Canada (1974), the first woman appointed to the Nova Scotia Supreme Court (1977), and the first woman named chief justice of a Canadian court (1982).

Constance R. Glube led the Supreme Court into the twenty-first century. She was born in Ottawa on November 23, 1931, and received her undergraduate education at Montreal’s McGill University. She completed her law degree at Dalhousie Law School in 1955 and was admitted to the bar the following year. She practiced in Halifax for four years before joining the legal department of the City of Halifax in 1969. A series of firsts followed – the first woman to be a city manager in Canada (1974), the first woman appointed to the Nova Scotia Supreme Court (1977), and the first woman named chief justice of a Canadian court (1982).

Glube served as chief of the court’s trial division until June 1998, when she succeeded Lorne Clarke as chief justice of the Court of Appeal and the province – another Nova Scotia first for a woman. Held in high regard for her administrative abilities, she has served on a number of committees of the Canadian Judicial Council and was a leader in the development of educational programs for judges. Glube retired from the Bench on Dec. 31. 2004. She passed away 11 years later, on Feb. 15, 2016.

For more information on Constance R. Glube, see profiles published by Dalhousie University's Schulich School of Law and Capital Heritage Connexion.

J. Michael MacDonald 2004-2019, Twenty-second Chief Justice

J. Michael MacDonald was born in 1954 in Whitney Pier, Cape Breton, where he lived all his young life. He earned his B.A. from Mount Allison University, his LL.B. from Dalhousie University, and was called to the Nova Scotia Bar in 1979.

MacDonald practiced his entire career as a lawyer in Sydney, Cape Breton, with Boudreau, Beaton & LaFosse, which later merged with Stewart McKelvey Stirling Scales.